Marxiano.melotti(at)unimib.it

Télécharger ce document (pdf 283 ko)

- Spartacus’ sons

During the nineteenth century there was an explosion of activities in costume and historical re-enactments of some special events. They enriched the processes of identity construction and made the reinvention of the past much more effective, also thanks to their experiential character.

In the nineteenth century Germany created a wide range of legendary heroes. The first and most important was Arminius, the Germanic warrior who in 9 A.D. overwhelmed three Roman legions in Teutoburg forest. Renamed “Hermann” (since the time of Martin Luther, who wanted to make him a symbol of the struggle of the Germanic peoples against Rome) and reinterpreted as the champion of German independence, Arminius became a mask of power, worn from time to time by some of Germany’s most prominent political leaders, such as Wilhelm I, the founder of the new German Empire, and Adolph Hitler, the founder of the Third Reich.

The other great mythical character that emerged in the same period was Spartacus, the slave who rebelled against the power of Rome. This figure was incredibly successful and was immediately used to support a wide range of cultural and political claims.

Marx (1861), who drew on Appian’s Roman History, described Spartacus as “the most brilliant [famoseste] character in ancient history”, “a great general, much better than Garibaldi”, and “a noble person, truly representative of the ancient proletariat”. A gladiator, expression of a society that regarded war and slavery as insuperable natural institutions, became the hero of the new proletariat in its struggle for social emancipation: an instrumental use of history, involving an “arbitrary extension of the paradigm of classes and their (possible) forms of consciousness”, since Spartacus could not aim at abolishing slavery, Schiavone (2011, p. 75).

Marx was writing in a period of profound economic, social, political and cultural transformation. In Europe the proletariat was forming its class consciousness ‒ or at least Marx thought so ‒ while the great nation-states were developing or gaining strength. Classical antiquity appeared as an inexhaustible reservoir of models and ideas to explain the present or even to shape it.

There are many examples of uses of the past for political and identity purposes. The figure of Spartacus was one of the most used in this way (Futrell, 2001). Long before Marx, in 1760, Bernard-Joseph Saurin, philosopher and playwright, made him a hero of the Enlightenment, who defended “the nature of human beings against absolutism”. In 1770 the Histoire des deux Indes, a work partially written and edited by the Abbé Raynal, invoked a new and “Black Spartacus”, “to throw over slavery” (even making the hypothesis of a vengeful replace of the black code with a white code). In 1791, when in Haiti the slaves revolted against the French colonists, their leader, Toussaint Louverture, was called the “Black Spartacus”. In 1809 the young Franz Grillparzer, an important Austrian dramatist, inspired by the Tyrolese rebellion against Napoleon, made him a nationalist hero, “hope of the fatherland”. In 1831 an American playwright, Robert Montgomery Bird, in a tragedy, The Gladiator, treated him as an “American hero”, because, in his opinion, he embodied the spirit of rebellion against the oppressors which had inspired the struggle for freedom and independence of the American colonies.

There are even more dramatic examples. In 1918 Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht called Spartakusbund their radical left-wing movement, inspired by a Spartacus “holding the sword of the revolutionary struggle” (Luxemburg, 1916) and fighting as “fire and spirit, heart and soul, will and action of the proletarian revolution” (Liebknecht, 1919). In fact, they treated him as a precursor of the struggle against modern imperialism, which Rosa Luxemburg had thoroughly analyzed and harshly denounced. Their revolt, however, ended tragically: both of them were killed, like Spartacus. This was probably the moment when his myth reached its apex in modern times. Their death wrested Spartacus from legend and threw him into the political arena, showing that there were still gladiators in revolt against the system and ready to die for their ideas.

All of these examples show a similar use of history: the past becomes a mask for the present and an identity and political tool.

- The Birthday of Rome and the carnival of power

Of course, this did not happen only in Germany. Even in Italy, which was still trying to build its national identity, we find a use of similar tools. From this point of view the history of the celebrations of the birth of Rome allows us to reflect on the cultural and political transformations of the city.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, when the unification of Italy was yet to be achieved and Rome was only the capital of the Papal State, that anniversary was celebrated almost exclusively by foreigners living there. Probably it was merely an occasion for revelling, with no political significance: in fact, it was a part of the Roman Carnival, which exploited a fictitious historical date for amusing and transgressive pursuits. Foreigners gathered in a cave to joke and perhaps philander in an atmosphere consistent with the primitive and romantic image that they had of the charming but backward Italy they visited on their Grand Tour.

These celebrations of the birth of Rome show the different way nationals and tourists use land and its image. For the temporary guests the civic space of the local community is an “other” world, which can be easily used for special activities with a playful or identity character. Especially before the Italian unification, Rome, with its crumbling ruins and its unique rural and pastoral views, depicted by the artists of the Grand Tour, was an area particularly suited to stage the para-initiatory activities which were part of proto-Romantic and Romantic cultural tourism. In fact, the city was a sort of large theme park or, rather, a place that hosted the set of complex functions that are now concentrated in theme parks. The bewilderment with which the local community witnessed, as it still does, the transformation of urban space is hardly surprising. At least before the “carnivalization of society” (Melotti, 2010), a similar change was allowed only in some specific situations with a ritual or semi-ritual character, such as Carnival, where it served the purpose of maintaining or restoring a social and psychological balance in the population, with beneficial political effects for the persons in power.

In the nineteenth-century the first celebrations of the birth of Rome had mostly a carnival character that breached the established order. But, as they emanated from foreigners, they were neither really appreciated nor understood by the local community. Indeed, they were mainly a Carnival of the foreign artists in Rome, in which also some Italians took part. The Spanish painters and sculptors organized an odd kind of cavalry by riding donkeys, the German artists represented the artillery by using wooden guns and the Italians were the infantry and took care of the victuals. The various armies met at the Cervara Tower, where they had a mock siege and battle, which culminated in a great banquet (Brigante Colonna, 1941; Venditti, 2007).

A historian who in the fascist era described those feastings condemned their alien origin and their playful character, which trivialized and derided the military element, almost inescapable in any Roman-themed re-enactment. But he captured the carnival character of those celebrations, where “the masks assumed a military aspect”. The festival was a great “masked” event that gave rise to a “carnival of reckless light-heartedness” (Brigante Colonna, 1941).

His words enable us to see how the commemoration of the historical events is constitutively marked by a basic ambiguity: what is in disguise can be either a carnival or a celebration. Power for centuries has used festivities ‒ and particularly the carnivals ‒ to control and channel impulses and social tensions that might undermine the system; for this purpose, power can accept a periodical suspension of the usual order and hierarchy. Thus the “people” can themselves put on the mask of “power”, provided that this disguise is only temporary. Similarly, power can give people panem et circenses (bread and circuses): it offers festivals and grand public spectacles which, together with amusement, show its coercive, economic and punitive strength. This may cause an uncontrollable short circuit: the historical re-enactment, as well as the military parade in costume or any other exhibition of military force and historical continuity, moves along the dangerous side of amusement: this, on the one hand, makes power acceptable and frightening, but, on the other, shows its basic weakness and its transience, which make it easier to mock.

The situation changed in the following decades with the evolution of the political context. The first “serious” Birthday of Rome was celebrated on April 21, 1847, when a group of liberals organized a celebration, with embryonic forms of living history and Roman-themed activities inspired by Romulus, Numa Pompilius and the Capitol She-wolf. “On Mount Esquiline, near the Baths of Titus, a great banquet took place: tables were arranged all around, so as to form a large seven-pointed star, seating about 800 diners. At the centre […] there were the statues of Romulus and Numa Pompilius. The whole scene was dominated by a warrior statue of Rome, with the She-wolf suckling Romulus and Remus at its foot” (Il Natalizio di Roma, 1847).

Lights in the Colosseum. Celebrations for the Birthday of Rome, 1849.

Museo Centrale del Risorgimento, Rome.

The organizers of this celebration were protesting against the lack of authenticity of the other feasting. In the new cultural and political scenario, they intended to trace a clear distinction between the Birthday of Rome and the Carnival. In 1848, “the liberal movement, wanting to change the traditional feasting from a revelling and impertinent event into a civil and celebrative one, in a short time succeeded in severely restricting the wildness of the Carnival and in wrecking the burlesque celebration of the birth of Rome” (Nasto, 1992, p. 334).

In 1849, after the proclaiming of the Roman Republic, the new city-state in search of an identity in stark contrast with the Rome of the popes, recouped the memory of the old Roman Republic. In this context, it invented ‒ or, rather, “reinvented” ‒ the festival of the Birthday of Rome. On April 21, the Colosseum was brightly lit with lamps and flares and a torchlight procession passed through the Forum.

But it was Mussolini who “hogged” Ancient Rome to shape the identity of fascist Italy and then of its Empire. Mussolini gave visual consistency to the assumed continuity between the past and the present (Giardina & Vauchez, 2000; Salvatori, 2006; Melotti, 2008; Terry, 2011). His instruments were new archaeological excavations, new museums, new specific university chairs, new large-scale architectural constructions and urban planning, including the reorganization of Ara Pacis Augustae and the opening of Via dell’Impero (Avenue of the Empire), now Via dei Fori Imperiali (Avenue of the Imperial Forums), and the bimillenarian celebrations of Virgil (1930), Horace (1935) and, particularly, the Emperor Augustus (1937).

Towards a new Empire. Mussolini and the Colosseum.

Poster of the “Mostra Augustea della Romanità” at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Roma, 1937

In this complex and varied work of reviving Roman heritage ‒ both in its material and immaterial dimensions: archaeological sites, monuments, architecture, literature, myths, traditions and values ‒ the creation of the magnificent Via dell’Impero certainly stands out. This majestic avenue connects two major symbolic poles of the city: at one end, Piazza Venezia, which houses the relatively recent Altar of the Fatherland (a monument to Vittorio Emanuele II, the King who unified Italy, and to the Unknown Soldier) and Palazzo Venezia, with its famous balcony from which Mussolini harangued the crowds; and, at the other end, the Colosseum, symbol of the might and ability of the ancient empire, and, for centuries, undisputed landmark of the city.

Parade along Via dell’Impero during Hitler’s visit to Rome (1938).

The creation of that avenue entailed the demolition of an entire neighbourhood of medieval buildings and monuments, with an implicit distinction between “strong” historical periods, worthy of recognition, and “weak” historical periods, which could be quietly forgotten. That operation had a clear ideological function: the regime prepared a great stage to celebrate itself, where the most impressive Roman building that had survived the ravages of time served as grand theatrical scenery.

The dramatic action of the regime took place in a historical context and was historically “themed”. Via dell’Impero ‒ container and showcase suited to host and display grandiose civil and military parades, but at the same time archaeological walk and tourist site overlooking the forums and the monuments built by kings, consuls and emperors ‒ was and is a real theme park: an artificial space using history as an identity factor and a vehicle for education and entertainment. It is not by chance that it still hosts the annual national military parade and receives hundreds of thousands of school students on cultural pilgrimages and millions of tourists in search of exciting archaeological experiences, not to mention historical parades and performances of living history. Thus this avenue has become deeply rooted in collective imagery and has helped to define the grand and imperial idea of Ancient Rome, which has become familiar owing to the fascist political rhetoric and then to the cinema’s visual rhetoric. It is this image that we expect to see, when we approach the Roman world. Though opened only in 1932, this avenue is globally seen as an “authentic element of the landscape of Ancient Rome” (Giardina, 2013), which the cinema has seized on and exploited, suggesting, as in The Gladiator, parades of legionaries along similar avenues.

In this huge and complex work of construction of a Romanized state and imagery, Mussolini used living history, with great parades in Roman costumes and Roman-themed events. But, first of all, Mussolini revitalized the celebration of the birth of Rome, on which he had already set his sights before coming to power.

In a speech in Bologna, on April 3, 1921, the future Duce had defined the ideological traits of this festival: “The Socialists have their May 1, the Popular Party has its May 15, and other parties have their own days. Also we, the Fascists, will have our day: April 21, the Birth of Rome. On that day, in the name of the eternal Rome, in the name of that city that bore two civilizations and will bear a third, we will recognize our identity and the legions of all regions will parade with our order, which is neither military nor German, but simply Roman” (Mussolini, 1921). The Birthday of Rome became a party celebration: the party took possession of that annual event to celebrate or, rather, to invent its tradition (Hobsbawm, 1983) and to launch its political religion (Gentile, 1990). Indeed, that festivity was a sort of patron saint’s day, devoted to Ancient Rome or, rather, to its image.

A few months before the March on Rome, Mussolini, in a speech that was published in his newspaper, stated that “to celebrate the Birth of Rome is to celebrate our civilization and to enhance our history and race” (Mussolini, 1922). He needed his mask and Rome provided it: “Rome is our starting point, our reference and our symbol or, if you prefer, our myth. We dream of a Roman Italy, wise and strong, disciplined and imperial”. The celebration of the Birth of Rome, with its Roman-style parades, became the disguise used to give visibility to the new imperial myth.

Living history here shows its extraordinary and dangerous myth-making strength: it creates and carves out a past to match our needs, and therefore with an ethnocentric and self-referring character.

In the same speech Mussolini stressed the importance of a “Rome of living souls”: almost unconsciously a living history able to give life to its monuments.

In 1923 Mussolini established the festivity of the Birth of Rome, which soon became nation-wide and absorbed the fascist Day of Italian Work and replaced May Day, the international labour holiday characterized by its leftish origin.

The enthusiastic words used in the fascist era to describe the celebrations of the Birth of Rome are extremely significant: “Labour and youth: there is no day more beautiful and holy than this, full of sacrifice, faith and hope. No longer masquerades. This is the festival of the peaceful and fighting labour. We lay hearts, banners and the Roman eagles on the Altar of the Fatherland” (Brigante Colonna, 1941).

The celebratory emphasis completed the metamorphosis of the festivity, which, from carnival event, turned firstly into a civil celebration, ideologically opposed to Carnival, and then became a nationwide event with nationalist and identity connotations. However, even this new festival, with its glory of eagles and flags, on the one hand involuntarily reacquired the original carnival character and on the other followed in the footsteps of Kaiser Wilhelm II, another imitator of the ancient Caesars.

The overlapping of the Birthday of Rome and Labour Day created an obvious cultural and political wound. Thus, soon after the fall of Fascism, the May Day celebration replaced that of the Birth of Rome, which once again became only a local and peaceful event.

- Photos and masks: the precarious gladiators of post-modern Rome

The gladiators change their mask. The past is no longer presented by the state as a political and educational model; it has become a sort of caricature used to thematize an experience (with increasingly recreational or tourist traits) fully immersed in the present.

The former masks of power are now reduced to masks of the past that operate without a power behind them. This is the case of the “ancient Romans for pictures”: the characters dressed as Roman gladiators, centurions or emperors that stand in front of the Colosseum, waiting to be photographed for a tip.

Tourists and ancient Romans at Colosseum (photo by M. Melotti).

Who and what are they? They can be regarded as figures linking the timeless dimension of the monument to ephemeral everyday life. They mingle with the vendors of global, multicultural and timeless merchandise, where the most various historical, political and religious elements appear confused and equivalent. The square in front of the Colosseum is a triumph of global tourist consumerism: stalls that, without any apparent distinction, sell little statues of Augustus, Michelangelo’s David, Totò, Padre Pio and Berlusconi; smiling illegal vendors who offer Chinese scarves with “Rome” printed on a picture of Athens’ Acropolis or t-shirts with “I love Rome” written with the red heart serially present on similar objects all over the world; and intrusive vans that incessantly hand out drinks, sandwiches and chips only a few meters from the monument.

In such a context it is not easy to take seriously the lively cohorts of the Praetorian Guard, who, dagger in hand, chase tourists and pester women and girls. Of course, this is part of Italian folklore, which, despite the justified embarrassment or disappointment of the Italians themselves, since the time of the Grand Tour has been one of the main attractions of a trip to Italy. The success of this strange activity is proved not only by the many hundreds of visitors who every day enjoy being photographed with these characters, but also by the photos and reports published online.

A curious book, 101 Places Not to See Before You Die, devotes an entire chapter to the gladiators of the Colosseum. Its author presents the area of the Colosseum with its “crazy” gladiators as the 67th place in the world to stay away from. She writes: “Most of its gladiators are harmless, more interested in carrying on loud cell-phone conversations with their girlfriends than in accurately portraying Ancient Rome”. But their presence may become quite troublesome and may deeply affect the fruition of the monument. She gives an idea of what happens nearly every day in front of it: “‘Ah, Christians to kill!’, he shouted in English. He ran at us, trident raised, and grabbed me by the neck. ‘Come over here’, he said, gesturing forward to a fellow gladiator. ‘I love killing Christians’. His friend obliged, holding a plastic sword to my throat as the crazy gladiator pointed his trident toward my chest and yelled ‘Silicone, ha ha ha!’, as Mark snapped a photo” (Price, 2010, p. 159-160).

However, in a post-modern society, where most experiences go through images, the “gladiators for pictures” are elements almost inseparable from the monument and end up becoming “monuments” themselves. Willy-nilly, they are an important filter that helps to introduce the historical and archaeological monuments into the mental space of the users, reminding them that they are in a modern city, where mass cultural tourism takes place and where culture has becomes a commodity, but they are also in the heart of Ancient Rome. Certainly, this operation would require a historical mediation with a cultural background that has become ever rarer. A significant story seems to confirm it: the President of the Canadian Parliament on a visit to Rome, after seeing the gladiators at the Colosseum, asked when the deportation of the Romans took place and anxiously enquired about the fate of these “descendants of the aborigines” (Merlo, 2012). It is clear that, in a context of increasing loss of historical knowledge, our ability to interpret or decode histories and cultures has become quite tenuous.

We can condemn this “illegal folklore” and “stalking of the tourists”, like the then deputy-mayor of Rome (Garrone, 2010), and denounce this “souk at the Colosseum”, like some journalists (Merlo, 2012; Larcan, 2012-a); we can deprecate the perversion of language by these new gladiators, who speak the “language of tourism, which degenerates together with the Italian art cities” (Merlo, 2012); we can also point out, somehow derogatorily, that these gladiators “more than Romans are Romanians” (Brogi, 2012). But we must analyze these phenomena in a wider context of global rearrangement of the educational and training processes and single out the new role played by edutainment in our relationships with space and time, i.e. with culture and history.

These contemporary gladiators, like all of us, suffer the anxieties due to the new “society of uncertainty” (Bauman, 1999). A few years ago they called for an official register of their activity, to obtain a professional role or, rather, a professional mask. On the web there is significant evidence of this identity claim. In front of the cameras a centurion said: “We are historical figures, part and parcel of the Colosseum […]. We want to be catalogued, we are an attraction” (I centurioni, 2012).

They unknowingly take note of the new “liquid” character of society (Bauman, 2000) and claim a hybrid role, as both attractions and historical figures. In short, they move between leisure and culture, education and entertainment, and ask for the recognition of an edutainment role. However, they also react to the disintegration of the old “solid” society, which gave stable contracts and identities, and claim to be “catalogued”, like books, and to be put on something solid, like the shelf of a library. Finally – and this is perhaps the most intriguing aspect – they want the process of crystallization and folklorization of tourism to be realized: a process in course in the city and in the country, which reduces both historical monuments and activities in costume to iconic images and souvenirs (Melotti, 2013-b).

The latent conflict between them and the local administration degenerated into a real battle and they were temporarily driven away from the Colosseum. This grotesque war assumed paradoxical aspects: a handful of young men engaged in an irregular marginal activity, probably partly controlled by criminal organizations (Merlo, 2012), as many other things in Rome, demanded that their work be recognized. They declared that they were offended by the charge of carrying out unauthorized activities in protected areas and requested to be treated as workers and not as “masks”. They staged demonstrations in costume and occupied the Colosseum claiming their right to work, with the support of a celebrated Italian lawyer who had defended a real mask of Italian politics: the twenty times minister and seven times premier Giulio Andreotti, nicknamed Divus Julius like Caesar.

With these actions the Colosseum changed its status: from a stage for tourist activities, tourist icon and a kind of giant souvenir, whose miniatures fill shops and stalls, it once more became an identity space and a place of political negotiation, though in a post-modern context. Not by chance the demonstrators called for the return of their ancestral model: “Spartacus mayor of Rome!”, “Spartacus, lead us back to the Colosseum!”.

The modern “gladiators for pictures” invoked the help of the figure who started the myth of the gladiators. But what kind of Spartacus did they invoke? The rebel depicted by the ancient historians? Marx’s leader of the proletariat? Rosa Luxemburg’s revolutionary hero? Kubrick’s Christological and socialistic protagonist of Spartacus (1960) or, perhaps more realistically, the post-political and crypto-gay character of an American TV serial, Spartacus: Gods of the Arena (2011), which was broadcast on Italian television just in that period?

In a liquid society all of these models coexist and hybridize: facts and experiences lose their contours and blend into a new complex reality. Therefore, also the “solid” elements of Spartacus’ mythology appear to be old-fashioned and outdated. The “choice between good and evil”, to say it with Rosa Luxemburg, still made sense in the ’50s, during the Cold War, when Kubrick’s Spartacus was shot, but its screenwriter, Dalton Trumbo, on Senator McCarthy’s blacklist, did not appear on the credits of the film. Since then our approach to history has increasingly become emotional and poor in content. The past has essentially become a container of emotions, feelings and experiences, as satisfying as possible. However, the ideological and political function of Spartacus’ myth has not completely vanished: it has simply changed to suit the new context.

The fight against McCarthyism. Wallpaper of Kubrick’s Spartacus (1960).

Thus in the streets of Rome, perhaps in the wake of the TV serial mentioned above, Spartacus has reappeared as defender of these new “heroes” of contemporary precariousness, invisible to all but tourists. It does not matter that the new rebels wear the costumes of those Roman soldiers that Spartacus fought, in history and films, and that many of them probably know him only thanks to the TV serial. He is not a political “model”, but an “image”, useful to “thematize” a battle and to attract the attention of the media.

First and foremost, history is a space for negotiation: a huge container of experiences, images, moods and sensations to decorate or enrich our world. The “gladiators for pictures” unknowingly resume Spartacus’ myth and, probably not less unknowingly, assume the new culture of body and senses, which Spartacus embodies in the TV serial, where he satisfies many explosive emotions and widespread needs. He gives an illusion of strength and security, and offers a successful model for everyday life: sex, fun, force and, why not, beauty and body care.

This emotional and pre-political revival of the myth of the gladiator does not “consume” the history of Ancient Rome, but rather its atmosphere. Anyhow, it revitalizes an idea that was deeply rooted in both ancient-Roman and Romantic imagery: the gladiator as a figure of contact between the worlds. Being continually on the threshold of death, he shows a special charge of vitality and sensuality.

A sexy hero. Poster of Spartacus: Gods of the Arena (2011).

However, the serial, in its glossy exaltation of muscle, sweat and blood, maintains much of the traditional view of Ancient Rome history, which is present both in the gaze of the tourist and in the best historical films, where everything is carefully reconstructed and becomes a sort of living history and even edutainment.

In the website we can find one of the reasons for the success of this serial. Each item refers to strong forms of inclusion and experiential activities, which mix reality and virtuality, history and new media, amusement and identity: “Become a god of the arena”; “Be the next goddess of Capua”, “Upload a photo to create your own”; “Join the legions of Spartacus – become a fan on Facebook”. Spartacus’ myth is only a marginal element of a wider and more articulated whole at whose centre there is not the ancient warrior, but the modern viewer, who consumes that myth by identifying himself with gladiators’ stories of love and death, sex and violence. Thus let him join a satisfactory experiential system, which makes him feel less alone, as part of Spartacus’ legions. All this, moreover, without risks for the system.

Cinema and politics, reality and fiction are already nourished by the same images. In fact, we are witnessing a contamination and hybridization between the culture of entertainment, cinema imagery and politics.

An interesting expression of this blending is the Italian film Benur (2012), directed by Massimo Andrei: a bitter and unpretentious look at the present world of work, increasingly precarious and invisible, and particularly at the condition of modern gladiators. A former stuntman, rejected by Hollywood and Cinecittà (the hub of Italian film industry, which contributed so much to the myth of the gladiators) contacts the racket and buys a job as a centurion in front of the Colosseum to earn his living; then he subcontracts a Slav, who becomes for him a sort of slave, in real Roman fashion. The film includes several scenes in costume at the Colosseum and the Circus Maximus, with a lot of getaways in a chariot, along the lines of the famous Ben Hur (1959) by William Wyler. During the filming some actors were mistaken for centurions of the Colosseum and some tourists asked them to pose for a picture. This short circuit between different levels of reality continued at the inaugural showing, with the red carpet, the chariot of the film and an exhibition in costume by a group of historical re-enactors, whose spokesman proudly pointed out that they had “nothing to do with the so-called gladiators of the Colosseum” (Montini, 2012).

But the most curious mix between reality and fiction was perhaps a recent comment by Russell Crowe, the Hollywood star who played the intrepid protagonist in Ridley Scott’s film The Gladiator (2000). In 2008, during an excavation along Via Flaminia, some workers discovered the remains of the tomb of Marcus Nonius Macrinus, the Roman general he had interpreted. In 2012 the Superintendent, for lack of funds, announced that the monument would have to be reinterred. The actor, outraged by the lack of respect for the grave and amazed by the inability of the Italian authorities to appreciate a site that – thanks to the film – could become of considerable tourist interest, made an outcry, while the American Institute for Roman Culture launched a petition to save the tomb. Hence TV crews from all over the world invaded the archaeological site and some Italian politicians denounced that “worldwide disgrace”, forcing the Ministry of Culture to ask for a detailed report (Larcan, 2012-b). Politics showed its subordination to the power of fiction and its glorious masks, while tourism and cinema affirmed their inescapable role in the new territorial governance.

- Totti, the last gladiator

In this proliferation of gladiators and legionaries, one of them stands out and has become a model for all the others: the captain of the Roma football club, Francesco Totti. In 2001, he swore he would have a gladiator tattooed on his right arm if his team won the Italian championship. Roma won and he kept his promise: his shoulder now shows the tattoo of a Roman soldier with his helmet, skirt and armour brandishing a dagger or, rather, a gladius. Since then Totti has been called “the gladiator”, a nickname that is added to others, such as “the eighth king of Rome”, inspired by the history of the city of his team. His gladiatorial tattoo seems to have increased the sales and rentals of The Gladiator, the film by Ridley Scott, released in 2000. The immediate success enjoyed by this film probably helped to revive young men’s interest in the Roman world, at least in its epic and warlike dimension, and suggested Totti’s investiture as defender of the Roman people or, at least, of the Roman team and its supporters.

From this point of view, the “gladiator” Totti is one of the outcomes of the modern reinvention of the past, with its use of the mask for celebratory and identity purposes. Once more we can measure the distance between the national and imperial rhetoric of the late Romantic age and the first half of the twentieth century. It used to be the kings and dictators who dressed up as ancient warriors to celebrate their power; now, in the post-modern society, it is the man-in-the-street who puts on fancy dress to celebrate himself. In short, nowadays football players (with other people affected by the same rhetoric) have replaced the persons in power.

The case of Totti, although conceptually sophisticated, is not based on any philological or historical study. This leads to an interesting mix of different cultures: in the web we find a rage of hybrid images, where, for example, the “gladiator” Totti is represented with the armour of a Greek hero, Achilles, protagonist of the film Troy by Wolfgang Petersen (2004). This short circuit between images and imageries confirms the liquidity of media culture and educational contexts, and also shows the deep interchangeability existing in European culture, not only in the present, between Greek and Roman elements. The Romantic rhetoric and the contemporary film industry have made these different civilizations two hardly distinguishable parts of the same world in costume, where, among white columns and impressive monuments, warriors fight and die with sandals, robes and stubby swords.

The tattooed body of Totti, new hero of contemporary society, has given rise to emulations that have re-launched some of the main symbols of Ancient Rome. On the web there are pictures of complex tattoos crisscrossing Totti’s face with armed legionaries staring unnervingly, she-wolves with Romulus and Remus, and flags with the Latin initials SPQR (Senate and People of Rome). Similarly, the International Tattoo Expo, which took place in Rome in 2011, chose as its logo a skeleton disguised as a Roman soldier, with helmet, shield and a mantle stained red from the spurts of blood of the tattooed.

Tattoos and Roman culture.

Gladiators at the Birthday of Rome celebration in 2015 (photo by M. Melotti)

Before the debates on the 150th anniversary of the Kingdom of Italy (2011) and the transformation of the Municipality of Rome into a new local authority named “Rome Capital” (2010), which entailed a rediscovery of Italian history and especially of the history of Ancient Rome, it was Totti that raised the symbols of Roman might outside the city, at the national level and in contexts not necessarily affected by nationalistic ideas. However, we must not forget that a political culture which explicitly or implicitly refers to fascism and uses the Roman symbols in line with Mussolini’s model still flourishes among young people in Rome. Black graffiti, such as “Since 753 B.C. masters of the world”, or posters with pictures of the Colosseum with fasces and male bodies in statuesque poses characterize the Roman urban landscape.

- Historical re-enactment and power today

In a liquid society each of its elements is confused, changes and loses shape; yet, sometimes, surprisingly, it resumes its form and consistency. Thus, the Municipality of Rome, while waging war with the figures in costume standing in front of the Colosseum, brought the celebration for the birth of Rome up-to-date.

With a mixture of local pride and universalist ambitions, championing football populism and political and identity convictions, the then mayor of Rome, Gianni Alemanno, a politician with a fascist background firstly funded the celebrations in costume for the Birth of Rome and then, in 2012, organized the celebrations for the 1700th anniversary of the battle of the Milvian Bridge, where on October 28 in 312 A.D. Constantine defeated Maxentius. On the same October 28, in 1922, the fascists concluded their march on Rome with a triumphant entry into the city: a date that, together with the Birth of Rome, entered the “liturgical” calendar of the Fascist civic religion (Gentile, 1993).

Even for this, Alemanno’s decision could not avoid the ironies of the press: “The new mayor of Rome, during his first year in office, came down from the Capitol to celebrate the Birth of Rome with all the honours due to the event and, under an ominous leaden sky, as a general before the battle, reviewed the troops of centurions, legionaries, gladiators, senators and handmaidens that had been lined up in the Circus Maximus” (Longo, 2012).

In recent years the Birth of Rome has gradually gained prestige. It has remained a local celebration, without any national ambitions, but it has become increasingly appreciated not only by foreign tourists (who, as we have already mentioned, expect such events, in line with their folkloric view of Italy), but also by the local community and even by scholars.

Historical re-enactment in Italy is now undergoing a sensitive and complex change (Melotti, 2013-a). For a long while it was almost completely neglected by institutions and scholars and was left to the initiative of volunteers. But its refinement in some countries (especially the United Kingdom, Germany, France and Spain) has exerted a good influence: its quality has gradually improved and even some scholars have begun to give their advice or even to use it. Museums and archaeological sites, in a context where teaching and traditional historical communication exert much less appeal than historical edutainment, offer more and more installations or exhibitions of living history in real or virtual form. The local authorities, aware of the increasing interest in it and addicted to the festival culture, in spite of the decreasing resources, support a plethora of initiatives in costume, whose quality depends only on the sense of responsibility of their organizers.

In other countries living history is an important tool, rooted in the territorial policies, encouraging the dissemination of historical knowledge. This, for instance, happens in Spain with “Tarraco Viva”, a Roman-themed festival created more than ten years ago in Tarragona to support its inscription on UNESCO World Heritage List (Seritjol, 2008; Melotti, 2013-b).

It should not be forgotten, however, that living history has its roots not only in experimental archaeology but also, and perhaps primarily, with its experiential, sensory, emotional and identity components and its mix of learning, fun, popularization, self-affirmation and group activities. Living history means amusement but also research, staying together with friends but also spreading knowledge to others: in one word, edutainment.

In Rome, since 1994, an association of re-enactors, the Gruppo Storico Romano, every year, on the Birthday of Rome, organizes a series of events in costume that represent the most vibrant part of the celebration. These activities have never obtained an explicit institutional support, but they have been very successful thanks to the passion and tenacity of those who have continued to propose them.

The most spectacular moment is certainly the procession with centurions, legionaries, vestal virgins and matrons, which, since 2003, goes along Mussolini’s avenue of the Imperial Forums. The warriors of the fascist Italian Empire have given way to these figures that parade for tourists and other spectators. This new festival has created its own traditions, such as the procession with the Goddess of the Waters bearing a chest, which, as explained in the website by Gianmarino Colnago Maurilio (stage named Gaius Cilnius Maecenas), holds the “ampullae with the waters of the sources of the great rivers where Italian civilization was born”: a “unique heritage”, since “they shaped our peninsula and our archaic culture”.

The new Maecenas and the Goddess of waters

during the celebration of the Birth of Rome (courtesy of G.M. Colnago).

The words addressed by this modern Maecenas to the user of the website are quite interesting: “Linger and dwell upon this heritage, which belongs to you […]. I dedicate these waters to anyone who will reflect on the intrinsic value of our common Italic matrix. Now stimulate the search of your deep cultural roots, take care of them and hand them respectfully on the posterity, whose future depends on them” (Le sacre acque, 2008). The ceremony itself has an undeniable unitary meaning: the waters of the whole of Italy implicitly contrast with those of just the River Po, contained in an ampulla at the centre of another symbolic ceremony with secessionist features, connected to the political demand for the independence of Padania (the part of Italy crossed by that river), popular until a few years ago in Northern Italy.

However, it also shows a desire to teach, which puts this masked festival in the sphere of edutainment. This commitment of the group is also proved by its small museum, its numerous educational activities of experimental archaeology and its “gladiator school”, a sort of gym for today’s gladiators but also an innovative space of socialization for the local community.

But we must not forget the other aspect of living history, entertainment, important not only for the spectators, but also for the actors. Yet, everything is plunged into a cultural landscape, which, in the last two decades, has been increasingly leisure-oriented and has paid increasing attention to the media. Hence “the competition to become the Goddess Rome”, which “annually tries to chose a girl who can embody the spirit of that Goddess, so dear to the ancient Romans, who loved and admired their city to the point of regarding it as a true living Goddess” (La Dea Roma, 2013). Of course, out of respect for both ancient history and modern “political correctness”, the competition is open to all “girls born or resident in Italy or in any country that once was a Roman province or protectorate”.

In recent years, the Birth of Rome has become more and more important. Accordingly to its organisers, the 2015 parade was performed by 1,700 re-enactors from ten European countries.

New legionaries’ parade in Rome (photo by Marten253).

New legionaries in front of the Colosseum (photo by Vincenzo Ricciarello, Gruppo Storico Romano)

Another attractive event was the celebration in 2012 of the anniversary of the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. “That battle”, as stressed the mayor Alemanno, “represents an epochal transition not only for Rome, but for the whole of Christianity, regarded as the bedrock of European civilization and identity” (Ponte Milvio, 2012). Once again, we can observe an overtly political use of the event, which retrieves the old nationalism though in a new European version. According to the mayor, “such an important event in the history of humanity” had to be remembered not in an “oversimplified way” but “with uprightness, seriousness and sobriety” (Anno 312, 2012). The downsizing of many public events, which characterizes the present political and cultural phase, makes a further difference with respect to the celebratory rhetoric of more or less recent history. The great parade originally planned has been replaced by a smaller event in a peripheral location: the reconstruction of a castrum at Saxa Rubra, with the participation of some prominent scholars and some activities carefully organized by SPQR, an association “well-informed about history”, which had collaborated with some major TV channels and programmes (National Geographic, History Channel and Ulysses). It simulated the battle with “perfectly reproduced” costumes and weapons, according to an educational model already experienced in many European countries, primarily the United Kingdom (In hoc signo, 2012).

The edutainment-oriented approach is quite evident. However, the reference to cinema and television, which have now replaced the academic world as authority-givers, should be stressed.

In addition, we must recall the specific role played by the cinema in the construction of the visual imagery connected to Roman civilization, as well as the close relationship existing in Rome, owing to the presence of Cinecittà, between the companies producing films in costume and the workshops of the city, the “underground” world of extras and, more recently, the associations of historical re-enactors. Indeed, a system of cross-contaminations has been created: Hollywood and Cinecittà “hybridize” with historians and other scholars, while dramas give visibility to the work of amateurs, who, in turn, “give life” to fiction.

A gladiator school in Rome (photo by Vincenzo Ricciarello, Gruppo Storico Romano)

Gladiators posing before the Colosseum, Birthday of Rome 2015 (photo by Valentino Mattei)

The SPQR website (Ludus Magnus, 2012) documents the serious and varied activity of this association, which is a good example of edutainment and innovative entrepreneurship. Its president, Giorgio Franchetti, provides an overview of its work: “Our athletes spent a long preparatory period in libraries, researching ancient texts and literary and iconographic sources, singling out the classes of gladiators which were typical in any period, in order to leave little to imagination or Hollywood reminiscences. For nearly two years we studied the documents and, in the meantime, for two hours a week, we trained to familiarize ourselves with pieces of gladiatorial equipment that were completely unknown to us […]. It was a sort of experimental archaeology, where we even had to understand how to use the instruments (almost all fakes of findings from Pompeii, carefully reproduced in weight and size), because no manual of gladiatorial combat has come down to us” (Todisco, 2011). This group has its own museum and a Gladiator Historical School, “open to women”, which even issues a “diploma”. Its presentation in English reveals the tourist ambition of the school and the fact it unfairly defines it as “the only one in Rome” sheds some light on a world of associations not only in search of their legitimacy but also in competition with each other.

- Concluding remarks: from the feast to the farce.

In order to conclude this reflection, it is worth recalling the parties organized by some members of the Council of Latium, the region of Rome. In particular, in 2012, the attention of the press was captured by a party, private but with prominent political figures, which clearly shows this interconnection between politics (in the traditional form of the election dinner) and festivity, in the case an amusing and light-hearted party in costume.

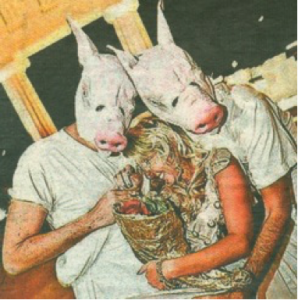

Some photographs taken at the request of one of its organizer (a member of that Council, Carlo De Romanis: nomen omen) clearly show the spirit of the party: men and women dressed as Greek and Roman warriors, with helmets and boots; sensual handmaidens offering grapes to young people languidly lying on the steps with bottles of champagne in their hands, men in drag with huge blonde wigs, smiling girls crowned with laurel, men wearing masks of pigs or minotaurs (Favale, 2012).

The masks of the power: political party in Rome

(photo published by Il Secolo XIX, 29 September 2012).

Greek and Roman antiquity is no longer thought of as a political and military model (we are very far from the spirit that inspired the Saalburg fortress). It is used only as a repertoire to thematize some experiences of sensory leisure. Once again it is a “relative” antiquity, where everything is confused, as in Totti’s figure, at the same time Roman gladiator and Greek warrior. That Roman-themed party was actually a celebration of the Greek Ulysses, in which Roman centurions mingled with his travelling companions and Homer’s zoomorphic creatures. Masks and costumes were not so different from those of the centurions of the Colosseum and, at best, came from the wardrobes used by film-makers. Once more, politics, cinema and popular culture were mixed and hybridized.

Probably the most “Roman” element in these parties was not their historical theme, but rather their impact on public opinion. But what they have in common with the leisure activities of the ruling class of the Roman Empire was not so much the moral degradation in itself (denounced by many observers), but rather the flaunting of this rollicking degradation. Actually the “orgiastic” parties in costume served a dual purpose: to affirm an ethical and behavioural “otherness”, which also entails an assertion of status, and to create wonder. Power wants to delight and amaze.

The new leisure society: political party in Rome

(photo published by Repubblica, 19 September 2012).

The press has often made reference to “a Late Roman Empire culture” (Regazzoni, 2012). In fact, these parties recall the spirit with which many public events were then offered to the people. But we could also remember the “elegant dinners” (to draw on the definition applied to his parties by Berlusconi himself) organized by the Roman ruling class. In its luxurious summer residences in Baiae or Sperlonga, themed banquets were often offered in halls adorned with statues dramatizing Ulysses and his companions’ adventures.

The parties of the Latium politicians mark a symbolic point of arrival of the present amusement society. At the same time they show the hidden ties connecting the ancient and the modern practices regarding communication policies of the elite as well as the cultural reactions to them. Anyhow, the severe (and even contemptuous) judgment of the Italian press on their behaviour is not so different from that of the senatorial historiography, which, in the early years of the Roman Empire, criticized the behaviour of the new elite.

References

AGNEW, Vanessa, 2007, History’s Affective Turn: Historical Re-enactment and its Work in the Present, Rethinking History, 11, 3, p. 299-312.

ANNO 312. Costantino vince a Ponte Milvio. Il Campidoglio celebra l’anniversario, 2012, La Repubblica, Cronaca di Roma, 25 October.

BAUMAN, Zygmunt, 1999, La società dell’incertezza, Bologna, Il Mulino.

–, 2000, Liquid Modernity, Cambridge, Polity.

BRIGANTE COLONNA, Gustavo, 1941, Natale di Roma, Strenna dei Romanisti, Roma, Staderini, p. 1-4.

BROGI, Paolo, 2012, Asterix e Obelix contro i centurioni di Roma, Corriere della Sera, Cronaca di Roma, 15 April.

CAMPIDOGLIO, stallo sui falsi centurioni. “Ma se li autorizziamo, paghino le tasse”, 2012, Corriere della Sera, Cronaca di Roma, 10 April.

Dea Roma, 2013, in http://www.natalidiroma.it/Dea_Roma/Info_dea2012.html.

I centurioni occupano il Colosseo, 2012, Oggi, 4 April, video, http://www.oggi.it/video/notizie/2012/04/12/i-centurioni-occupano-il-colosseo/.

FAVALE, Mauro, 2012, Ancelle e mojito, De Romanis festeggiò vestito da Ulisse, La Repubblica, 19 September.

FUTRELL, Alison, 2001, Seeing Red. Spartacus as Domestic Economist, in Joshel, Sandra R., Malamud Margaret & McGuire, Donald T. (eds), Imperial Projections. Ancient Rome in Modern Popular Culture, Baltimore – London, Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 77-118.

GARRONE, Lilli, 2010, Via i questuanti mascherati dal Colosseo. Pronta una legge contro i centurioni, Corriere della Sera, Cronaca di Roma, 26 June.

GENTILE, Emilio, 1990, Il fascismo come religione politica, Storia contemporanea, 6, p. 1079-1106.

–, 1993, Il culto del littorio. La sacralizzazione della politica nell’Italia fascista, Roma – Bari, Laterza, 1993.

GIARDINA, Andrea, & Vauchez, André, 2000, Il mito di Roma, da Carlo Magno a Mussolini, Roma – Bari, Laterza.

–, 2013, Quella strada ormai nella storia non diventi parco giochi, Il Messaggero, 4 August, p. 1 and 8-9.

HOBSBAWM, Eric J., 1983, Introduction, in Hobsbawm Eric J. & Ranger, Terence (eds), The Invention of Tradition, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, p. 1-14.

In hoc signo vinces: dopo 1700 anni Roma rivive la battaglia fra Costantino e Massenzio, 2012, http://www.eventinelxx.it/in-hoc-signo-vinces/.

LARCAN, Laura, 2012-a, Fori e Colosseo, basta bancarelle e legionari, La Repubblica, Cronaca di Roma, 29 March.

–, 2012-b, Sos Tomba del gladiatore. Crowe “scatena” il web, La Repubblica, Cronaca di Roma, 11 December.

LIEBKNECHT, Karl, 1919, Trotz Alledem!, in Die Rote Fahne, 15 January, in Liebknecht, Karl, 1968, Gesammelte Reden und Schriften von Karl Liebknecht, vol. 9, Berlin, Dietz, p. 675-679.

LONGO, Federico, 2012, Ponte Milvio, 15mila euro per rievocare la battaglia di Costantino e Massenzio, Paese Sera, 20 September.

Ludus Magnus, 2012, http://www.ludusmagnus.info.

Luxemburg, Rosa, 1916, Die Krise der Sozialdemokratie, Zürich, in Luxemburg, Rosa, 2000, Gesammelte Werke, vol. 4, Berlin: Dietz, p. 51-164.

MARX, Karl, 1861, Briefe an Friedrich Engels, 27 February; in Marx, Karl. & Engels, Friedrich, 2005. Gesamtaugabe (MEGA), Berlin, Akademie Verlag, 3ª ed., vol. 11, p. 377.

MCCALMAN, Iain & Pickering, Paul (eds), 2010, Historical Reenactment. From Realism to the Affective Turn, London – New York, Palgrave Macmillan.

MELOTTI, Marxiano, 2008, Turismo archeologico. Dalle piramidi alle veneri di plastica, Milano, Bruno Mondadori.

–, 2010, Oltre il carnevale. Maschere e postmodernità, in Sisto, Piero & Totaro, Piero (eds), Il Carnevale e il Mediterraneo. Tradizioni, riti e maschere del Mezzogiorno d’Italia, Bari, Progedit, p. 57-88.

–, 2011, The Plastic Venuses. Archaeological Tourism in Post-Modern Society, Newcastle Newcastle, Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

–, 2012, Fantasie ibride. Il corpo e la maschera nella rete globale, in Sisto, Piero & Totaro, Piero (eds), La maschera e il corpo, Bari, Progedit, p. 262-283.

–, 2013-a, Turismo culturale e festival di rievocazione storica. Il re-enactment come strategia identitaria e di marketing urbano, in Deriu Romina (ed.), Mobilità turistica tra crisi e mutamento, Milano, Franco Angeli, p. 144-154.

–, 2013-b, Oltre la crisi. Il turismo culturale tra riscoperta delle radici e lentezza rappresentata, in La Critica Sociologica, 185, p. 51-66.

MERLO, Francesco, 2012, Gran suq Colosseo. L’antica Roma assediata dal kitsch, La Repubblica, 14 March, p. 31-33.

MONTINI, Franco, 2012, Red carpet tragicomico con il centurione Benur, in La Repubblica, Cronaca di Roma, 10 November.

MUSSOLINI, Benito, 1955, Speech in Bologna, 3 April 1921; in Susmel, Edoardo & Susmel, Duilio (eds), 1955. Opera Omnia di Benito Mussolini, Firenze, La Fenice, vol. 16, p. 244.

–, 1922, Passato e avvenire, in Il Popolo d’Italia, 21 April 1922; in Susmel, Edoardo & Susmel, Duilio (eds), 1956. Opera Omnia di Benito Mussolini, Firenze, La Fenice, vol. 18, p. 160-161.

NASTO, Luciano, 1992, Le feste civili a Roma 1846-1848, in Rassegna storica del Risorgimento, p. 315-338.

Il Natale di Roma: celebrato il XXI aprile MDCCCXLVII, banchetto pubblico sul monte Esquilino, Roma, 1847 (vol. 23031, Harvard Risorgimento Preservation Microfilm Project).

Il natalizio di Roma e Pio IX [printed sheet], 1848, Roma, in “Miscellanea” 22.6.C.2 1848, p. 2, Biblioteca di Storia Moderna e Contemporanea, Roma.

Le Sacre Acque, 2008, http://www.gsr-roma.com/museo/mecenate/acque.html.

Ponte Milvio, celebrazioni per i 1700 anni della battaglia, 2012, http://terpag.blogspot.it/2012/10/ponte-milvio-celebrazioni-per-i-1700.html.

PRICE, Catherine, 2010, 101 Places Not to See Before You Die, New York, Harper.

REGAZZONI, Simone, 2012, Basso Impero, Il Secolo XIX, 29 September, p. 1 and 4.

SALVATORI, Paola, 2006, La Roma di Mussolini dal socialismo al fascismo (1901-1922), Studi Storici, 3, p. 749-780.

SANS, Sara & Seritjol, Magí, 2008, Tàrraco Viva. Jornades internacionals de divulgació històrica romana, Tarragona, Arola.

SCHIAVONE, Aldo, 2011, Spartaco, Einaudi, Torino 2011 (transl. Schiavone, Aldo, 2013. Spartacus, Cambridge, Mass. – London, Harvard University Press).

SERITJOL, Magí, 2004, Tàrraco Viva: un festival internacional especializado en la divulgación histórica, Mus-A: Revista de los museos de Andalucía, 4.

SOLOMON, Jon, 2001, The Ancient World in the Cinema, New Haven – London, Yale University Press.

TERRY, Kirk, 2011, The Political Topography of Modern Rome. 1870-1936. Via XX Settembre to Via dell’Impero, in Caldwell, Dorigen S., Caldwell, Lesley (eds), Rome: Continuing Encounters Between Past and Present, Farnham, Ashgate.

TITTONI, Maria Elisa & Nicosia, Alessandro, 2007, La storia racconta il Natale di Roma, Roma, Gangemi.

TODISCO, Stefano, 2011, Intervista all’associazione culturale SPQR, Antika notizie», 23 September, in http:// notizie.antika.it/ 0010554_intervista-all-associazione-culturale-s-p-q-r/.

VENDITTI, Annalisa, 2007, La torre e le grotte di Cervara, Specchio romano, blog, February, in www.specchioromano.it.

Publié sur le site de l’Atelier international des usages publics du passé le 16 juin 2015